Fishers as stewards: generations of wisdom in Spanish and Scottish harbourside communities

- Georga Holly

- Feb 29, 2024

- 9 min read

Updated: Aug 13, 2024

Written by Annie Edwards, researcher with the Cultural Heritage Framework Programme/University of Edinburgh, and Fabric Media

“The sea is the most important thing, it’s part of my life, it’s everything... it is a vital cycle in our area and part of our identity”, says Federico* a fisher in Lira, Galicia, the northwest corner of Spain where the Atlantic’s wrath is formidable, the air pure, and forested mountains dotted with terracotta-roofed pueblos (towns) and Romanesque churches dip into the sea.

Winding between stacks of crab and octopus creels along Lira’s harbour, Federico waxes on el salitre (the saltpetre, salt residue) ingrained in every Galician: “I believe that el salitre was impregnated in each one of us, not since we were little, but since we were born”, as they live, breathe, and eat the ocean’s manifestations. Federico explains how the sea infiltrates everything from mealtime to the famous Galician hórreos (granaries) that historically dried conger eel and octopus, “Any food that you eat here has a link with the sea, any construction that is built has a link with the sea, any celebration that takes place, that is, the culture itself is sea… The culinary with the sea is everything. In all the festivities, Christmas, winter solstice, Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve, we eat seafood.”

As fishers spoke of their inner salitre, Sonia*, a mariscadora (shell fisher) harvesting mussels, oysters, and goose barnacles, elaborated that only the local language, Galician, describes what Spanish (or English, for that matter) cannot, “in Galician there’s a word ‘morriña’ for when you’re missing something, I feel morriña when I’m not near the sea.”

While my personal fishing catch record is pitiful and I can’t surf anything beyond white water on an 8’ glorified boogie board, I also feel el salitre within me, a sensation that radiates peace and joy when I’m near the sea. I spent some formative years in Santa Cruz, California, rock pooling with my mom and training as a “junior lifeguard” (something quickly forgone as it required sprinting and push-ups, we instead moseyed around Monterey Bay Aquarium). Every time I moved away from the ocean, by compulsion to Cleveland, Ohio or choice to Madrid, Spain, I too felt morriña. I needed white caps to quiet my inner storms and found myself learning to scuba dive in Ohioan pools and along Spanish coasts. Embracing the sea’s essential role in both my well-being and the world’s, I undertook an MSc in Marine Systems and Policies at the University of Edinburgh. However, during this programme, what captivated me wasn’t the ocean’s serenity, but its drama. Drawn to areas where human activity overlapped with marine worlds, I devoured books like The Outlaw Ocean and Kings of Their Own Ocean which explore the intricate relationship between humanity and the sea.

Fishers with answers

Anyone who is a friend of the ocean is a friend of mine, and I deeply respect and admire people whose livelihood is inextricably linked to the sea. In a world overly dependent on software updates and mobile crutches, artisanal fishers seem like super-people to me, relying on low-tech tools and their intuition to provide for their community while caring for the sea. So, for my MSc dissertation, I spent time in the traditional fishing communities of St Abbs, Scotland and Lira, Galicia, Spain.

Left: creels (“nasas”) in Lira, Spain. Right: creels in St Abbs, Scotland © Annie Edwards

Galicia is renowned for its seafood and rugged coasts. I travelled to Lira on the Costa da Morte, translating to “Coast of Death”, though locals affectionately refer to Galicia as “Gali-fornia”, perhaps a nod to its surf culture. Yet, far from the cliffs of Santa Cruz, I found that if I squinted, or perhaps forgot my jacket, Galicia may be mistaken for Scotland with its green hills, biting turn-your-toes-purple waves, and piles of creels haphazardly strewn around the harbours. Galicia is known as the 7th Celtic nation, and Galicia and Scotland share commonalities beyond their Celtic origins, as both economies rely on fishing and their Atlantic coastlines are dotted with traditional ports hauling species like crab, lobster, clams, and octopus with traditional fishing gear including creels, long-lines, nets, and even hand harvesting. While both coasts have fishing traditions dating back hundreds and thousands of years, they also have glimmers of a new wave of artisanal fisheries management and ocean conservation—Lira’s marine reserve was designated by fishers themselves, while St Abbs is home to the Berwickshire Marine Reserve, Scotland’s first and only voluntary marine reserve.

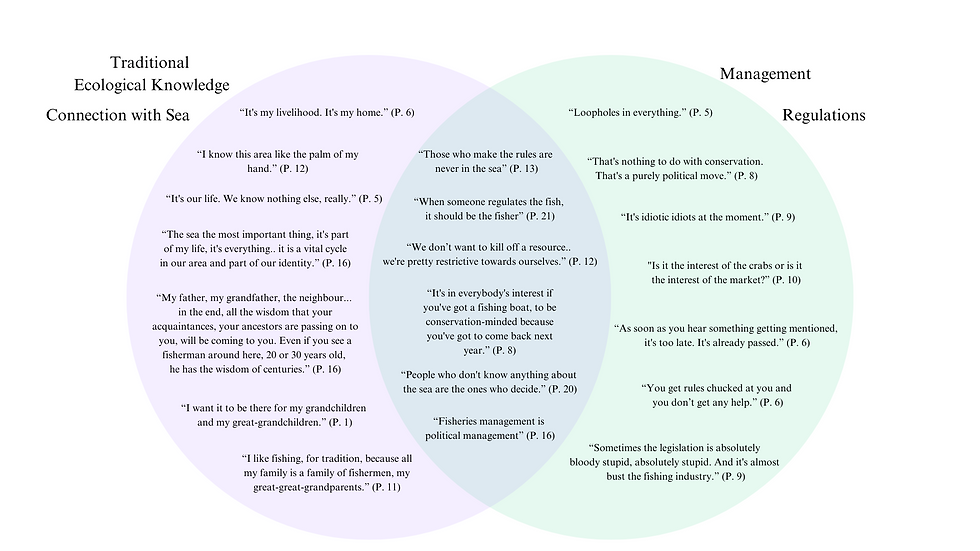

In both harbours, I spoke with fishers who held generations of wisdom, understanding the sea better than most could dream to, yet seemed inexplicably absent from the policy and management decisions that ruled their lives.

A guardian with no power

Artisanal fishers are increasingly regarded as the guardians of the sea [1], but is that all talk? Squeezed between industrial fishing fleets, expanding offshore energy infrastructure, and well-intentioned but occasionally poorly designed “no take zones” in Marine Protected Areas, these guardians often get the short end of the stick.

Arriving in quaint St Abbs, Scotland on a summer day, the atmosphere was tense. As Scotland looks to establish Highly Protected Marine Areas, the government is facing backlash from fishers. This disagreement and distrust has been brewed into the fabric of Scottish communities for generations, partially stemming from the Highland Clearances (forced evictions throughout the 1700s and 1800s), a term rearing its head with fishers singing the protest song “Clearances Again” to oppose the Scottish government’s Highly Protected Marine Area plans.

I collaborated with St Abbs Marine Station and Blue Marine Foundation to get in touch with the St Abbs fishers. During interviews, they expressed concerns such as: “I’m a bit concerned about these HPMAs”, "‘It’s idiotic idiots", “Sometimes the legislation is absolutely bloody stupid, absolutely stupid, it’s almost bust the fishing industry,” and “You get rules chucked at you and you don’t get any help”. These sentiments reflect a rift between policy and community consultation.

Galicia, Spain offers glimmers of hope, as the artisanal fishing sector is run by localised cofradías – translating directly to brotherhood. Cofradías are co-management organisations, meaning they’re operated by fishers, for fishers, in collaboration with the regional government. The Spanish cofradías date back to the 12th Century and account for 83% of Spain’s fishing employment, responsible for managing sedentary species (like razor clams and seaweeds) while the national Spanish government manages other coastal resources in line with the EU Common Fisheries Policy [1].

Working with Fundación Lonxanet, I’d chosen to interview fishers in Lira because this cofradía exemplifies the co-management of a marine reserve that allows fishing. In Lira the fishers themselves designed the marine reserve, setting aside off-limits juvenile grounds while other parts of the reserve have rotating seasonal closures. Overall, the Lira fishers seemed happy with the arrangement, saying things like, “Co-management is good because it is a formula in which we make decisions regarding what is ours.”

In Lira, a goose barnacle fisher shows his gear and the cofradía's barnacles processing © Annie Edwards

But it’s not perfect. Are the fishers’ voices always heard? Do they really have enough power, with the Galician and Spanish governments still setting most catch quotas? At the end of the day, Federico champions co-management, admitting he’s a bit of a visionary, but remarked “Fisheries management is political management” and questions why politicians in land-locked Madrid and Brussels are making decisions that should be left to the fishers, as another Lira fisher commented, “Those who make the rules are never in the sea”.

From St Abbs to Lira, while contentment ebbed and flowed, the disconnect between fishers’ stewardship and current management was impossible to ignore.

Generations of knowledge

Fishers are guardians not just of the sea, but of its surrounding cultural heritage. The term “marine cultural heritage” describes the evidence of past, present, and future human interactions with coastal and marine geographical or cultural areas, applying to tangible remains like shipwrecks but also intangible heritage like cultural practices, oral traditions, and fishers’ knowledge [2, 3]. There’s an increasing momentum for marine cultural heritage to be more integrated into management and policy, as it’s shown to drive sustainable development, engaging local groups and effecting community-level change, and thus is an essential element in achieving the UN Ocean Decade’s mission to “achieve the ocean we want” by 2030 [2].

Exemplifying fishers’ generations of wisdom, Federico told me that he learned fishing from generations before him: “My father, my grandfather, the neighbour... in the end, all the wisdom that your acquaintances, your ancestors are passing on to you, will be coming to you. Even if you see a fisherman around here, 20 or 30 years old, he has the wisdom of centuries.”

This was echoed in St. Abbs, where all but one of the fishers I interviewed had learned fishing from their father – with one fisher recalling that his family encompassed twelve generations of fishers.

However, the generational flow is ebbing in a new direction. Most of the fishers in Lira and St Abbs said their children were pursuing different career paths – some still tied to the sea, like yachting tours, while others were off studying business and medicine. Being a fisher is hard, and as top-down policies changed their livelihoods without consultation or notice, the next generation is hedging safer bets on drier ground. When fishing goes, the fishing communities go – the youngest fisher I spoke with in St Abbs was 29 years old, fishing alongside his father, while the rest were in their late 40s, 50s, or 60s, commenting that they don’t see a future for creel fishing in anywhere from ten to 50 years. While Britain’s seaside towns are bouncing with life during summer, they’re paradoxically depleted throughout the rest of the year, which is why some social enterprises are sprouting up like the Sea Ranger Service, which just launched in the UK to “train young people from predominately deprived coastal regions to become ocean conservationists, while paying them a salary.” Will coastal youths’ jobs shift from fishing to conservation, or perhaps a mixture of both?

Love of the sea

As guardians of the sea, fishers navigate the waves through winter’s rains and swells – it’s their life. In St Abbs, fishers reflected, “I like to wake up in the morning and watch the dolphins go down the coast or watch the killer whales. The ocean’s there for you”—and on why they should have more of a voice in management, they emphasised, “It’s in everybody’s interest if you’ve got a fishing boat, to be conservation-minded because you’ve got to come back next year... I want it to be there for my grandchildren and my great-grandchildren.”

Not to diminish the fierce efforts of fishers hauling lobster in the depths of winter from St Abbs Head, but the Galician mariscadoras (female shell fishers) stole my heart. This endeavour is treacherous, resulting in multiple deaths each year as it requires wading between skull-crushing rocks and crumbling waves to yank goose barnacles from rocks. Yet as I spoke to some of these women, they said ‘I like it, I wouldn’t trade it for any other job in the world. The sea gives you the feeling of freedom. That feeling of freedom? Yes, it is the smell of el salitre.”

Stewards and solutions

Conversations with the fishers were teaming with passion, teetering between frustration (with politicians) and love (of the sea). Fishing is as old as humanity itself. While Celtic mythology honoured salmon as a vessel of otherworldly wisdom, today Galicians are reflecting on their inner el salitre, while I browse #bluehealth and seek the sea as a reprise from screens. Despite thousands of years of history, the future of fishing is changing rapidly – artisanal fishers such as Federico face threats including industrial fishing, offshore energy, and policy changes. While many Marine Protected Areas are well-intentioned, they can forget to consult fishers like Federico who know the sea “like the palm of my hand” – resulting in ineffective or arbitrary boundaries while putting local communities out of work.

Fisheries management is people management. Over three billion people rely on fishing to make a living, 90% of which is artisanal fishing – representing billions of potential ocean guardians. Solutions are underway with the incorporation of cultural heritage in community-centred Marine Protected Areas in the Philippines, fishers leading shark conservation in Mexico’s Baja California Sur, and trials of fisher-led management in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland.

Everything is interconnected, and if we’re to coexist with changing seas and political tides, it’s essential to lean into the connections between culture, livelihoods, and marine ecosystems. Keeping lessons in mind from previous generations, it’s essential to engage the next generation – the youth are the ones leading climate activism, and who will be keeping harbourside towns afloat, potentially through initiatives like the Sea Ranger Service or by completely re-thinking our approaches to marine protection. As research advances “non-traditional” marine conservation models (like community and Indigenous-led marine reserves that allow for small-scale fishing) while younger people ditch traditional jobs, the tides of change feel promising. Looking at the future of coastal communities holistically, recognising their heritage and wisdom, enables multidisciplinary, collaborative solutions for the Ocean Decade. The past holds keys to the future, as currents ebb and flow, fishers should captain the change.

Annie with creels in St Abbs (left) and Lira (right) © Annie Edwards

*fishers' names have been changed

References

[1] L. Perez de Oliveira, ‘Fishers as advocates of marine protected areas: A case study from Galicia (NW Spain)’, Mar Policy, vol. 41, pp. 95–102, Sep. 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.12.024.

[2] J. Henderson, ‘Oceans without history? Marine cultural heritage and the sustainable development agenda’, Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 11, no. 18, Sep. 2019, doi: 10.3390/su11185080.

[3] J. Henderson et al., ‘Rising from the Depths Network: A Challenge-led Research Agenda for Marine Heritage and Sustainable Development in Eastern Africa’, Heritage, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 1026–1048, Sep. 2021, doi: 10.3390/heritage4030057.

Comments